[Originally published in GeneseeSun.com]

Bigger than Elvis – on the other side of the world

I have a major fetish for really great songwriters. Bob Dylan, Tom Waits, Joni Mitchell, Randy Newman, Jacques Brel, Stephen Sondheim, for starters … the list is exclusive, but it’s not terribly short. I consider myself to be something of a scholar in this area, or at least a really serious connoisseur. So I’m baffled and somewhat embarrassed to admit that, prior to this week, and prior to seeing the film I first heard about on David Dye’s NPR radio show World Café, I had never heard of Rodriguez.

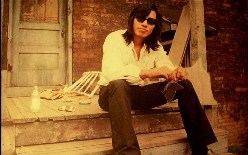

A powerfully evocative singer/songwriter active in the early 1970s, little-known in America, Rodriguez is the subject of the wonderful 2012 Swedish/British documentary directed by Malik Bendjelloul, Searching for Sugar Man. Rodriguez appeared in Detroit in the late sixties, circulated on the music scene briefly, released two albums to the high expectations of his label and his producers, and then vanished. Actually that’s not quite correct. He couldn’t vanish, because as far as industry bean counters were concerned, he never even appeared. According to the producers of the albums, who are interviewed in the film, here in the U.S. the LPs were each met with positive critical response but a deafening silence commercially. Nothing. And thus would have ended the tale – except that for some deeply karmic reason, at exactly that moment Rodriguez became, in South Africa at least, bigger than Elvis. Seriously.

Somehow the two Rodriguez albums, Cold Fact (1970) and Coming From Reality (1972), struck a major chord in 1970s South Africa. They were first picked up by musicians on the strongly censored Johannesburg music scene, and then by record shops and radio stations, and then, simply, by everyone. As one of the South Africans interviewed in the film described it, in those days three records were flat-out standards in every record collection of anyone even remotely knowledgeable about music: The Beatles’ Abbey Road, Simon and Garfunkel’s Bridge over Troubled Water, and Rodriguez’ Cold Fact. Conservative estimates are that the record may have sold over half a million copies – on the other side of the world.

The film chronicles the search by two major fans for the assumed-to-be-historic Rodriguez, about whom virtually no information whatsoever is available, other than the cryptic text on the LP labels and sleeves. It is, as they say, “a great musical detective story.” By using the Watergate-era trick of following the money, and by mining his lyrics for geographic clues, they eventually discover Rodriguez’ roots. Despite rumors of his death from causes ranging from gory on-stage suicide(s) to a drug overdose, the searchers [spoiler alert] are stunned to discover him alive and well in Detroit, where he has lived and worked quietly, zen-like, for decades, as an ordinary construction worker.

As a music phenomenon Rodriguez has undergone a deserved renaissance, in no small part due to this film. Searching for Sugar Man has garnered a host of festival awards around the world so far, including Sundance, Los Angeles, Durban, Melbourne, Tribeca, and Moscow. In South African concert tours organized after his 1998 re-discovery, which are part of the film, Rodriguez plays, Lazarus-like, to huge, joyous, tearful sell-out crowds. Re-releases of the albums are now available on CD from Amazon. There is an official Rodriguez website, Sugarman.org, and a Facebook page, and he continues to tour occasionally.

In addition to the quest itself, the film does a great job of laying out the fundamental oddity of the story: the total lack of popular response in his own country, and the stark contrast with his reception on the other side of the world. One thing the film does not do, however, is answer the almost mystifying question, Why? That’s actually not one, but two questions. One: Why nothing here? And Two: Why such a smash hit there? The answers have the man, and the music, as a common denominator. The answers, though, are as different as the two countries.

Here in the U.S., in 1970 there was a kind of musical vacuum in the singer/songwriter, protest wing of the popular music field. Dylan had recovered from a traumatic July 1966 motorcycle accident and didn’t perform live for eight years. With John Wesley Harding (1967), Nashville Skyline, (1969), and then Self-Portrait (1970), there was a growing sense that he was moving into strange territory creatively, but plainly away from the strident social and political criticism and the prophet-poet stereotype of his early years that had culminated in the near-hallucinogenic lyricism of Blonde on Blonde (1966). One would think that in this palpable absence Rodriguez’ music, which hit the same kind of button strongly, would have had serious appeal.

Rodriguez is not Dylan, though. For a superficial starter, he was the first example of a one-name celebrity that I can think of (Cher doesn’t count; she was originally part of a couple with a known last name, and hadn’t emerged as much of a solo act in 1970 anyway). And while his first name is one of the mysteries that the musicologists in the film try and decipher, his hispanic last name probably has more to do with the lack of success in America.

In thinking about Latino musicians, certainly in those days, cross-over artists were rare. The only significant contemporary I can think of was Jose Feliciano, and while the breadth, depth, and quality of Feliciano’s music was clear, if perhaps underappreciated, he was neither a Dylan nor a Rodriguez.

I think it’s no accident that Sixto Rodriguez came of age and surfaced musically, to the extent that he surfaced, in Detroit, motor city, Motown, where the racial aspects of the music industry were comfortable terrain. Producer Clarence Avant and Buddha Records seemed to understand better how to promote an African-American crossover like Bill Withers, though, than a Latino like Rodriguez. I think that Rodriguez, who critics and insiders seemed to like but who sold poorly, had a kind of quota problem. As far as ethnic cross-over artists go, in those days there was really only room for one “ethnic” in any one category at a time. Feliciano filled the quota for Latin cross-overs, and that trumped the poet/prophet vacancy.

Rodriguez’ enormous resonance in 1970s South Africa certainly stands on his creative and musical merits, but there’s much more to it than that. There has to be. He didn’t achieve that kind of reception anywhere else in the world, at least not then…just in South Africa. So why is that?

It’s impossible to separate the politics of that country – a global pariah and poster-child for segregation, at the height of the apartheid era – from the cultural environment that Rodriguez’ music fell into there. If anything, the pop culture environment in South Africa was at least as sensitive to political issues as it was here in the U.S., even as we were at the height of the Vietnam War protests. While the problem of race may have been a critical factor in Rodriguez’ failure here commercially, in South Africa, a starkly polarized country intensely preoccupied with matters of race, he simply did not register that way, as a racial “other,” at all. Of course, that may be true only when viewed from a white perspective; the filmmakers do not dig into this issue, and the film shows very few non-white faces among the Rodriguez fans interviewed or in the South African concert audiences.

At any rate, the white music community that tells the majority of the film’s story is not made up of status-quo, apartheid-friendly, establishment listeners. While his songs do not explicitly address issues of race, they resonated. His lyrics are are grounded in the gritty realities of Detroit street life, forceful social criticism, poignant calls for change, aggressive and lyrical at the same time. There is no better sign of the protest function of his music than the fact that some of the songs on his records (vinyl records in those days, by the way) were physically censored by the South African authorities by mechanically gouging the surface, which rendered those specific tracks unplayable. There’s nothing like being banned to get the attention of a bunch of young people bent on protest.

In a way, the World Café radio show was a better introduction to Rodriguez’ music than the film is, as the format for Dye’s radio program allowed a number of remastered songs from the original LPs to be played full-length. In documentary films about performers, the music frequently plays a somewhat secondary role to the storytelling. What comes through more fully on careful listening is the songwriting, the poetic and the musical voice itself – which undoubtedly had everything to do with the South African success story. It would be very hard indeed to find another songwriter in that cultural moment with the combination of musical ear, lyricism, poetry, and an extremely sharp sense of social criticism, who simultaneously captures the experience of heartbreak and loss, disillusionment and alienation, with a working-class sensibility.

The most moving aspect of the film, I think, is the spiritual dimension to the story, the two difficult experiences of finding, and accepting, one’s place in the universe at any given moment. There is the initial question of where a gift, a voice, like that comes from, how you find it, and how you feed it. But there’s a related question, possibly bigger, certainly more difficult. What happens when the thing that you’re doing, that you’re certain you’re supposed to be doing, seems to not work? When it seems like your gift doesn’t matter?

Rodriguez, the film says, gracefully accepted this apparent twist of fate, and found another place in the universe that seemed to be his, doing manual labor, an ordinary construction worker. He did this for nearly two decades before he was rediscovered by the South African fandom, alive and well, and brought back into the limelight. And in the same way he lived his life on the fringe, the concert footage shows a man at complete ease in his moment, this time performing on stage before many thousands of people. Where does that kind of grace and humility and acceptance come from, especially in the face of a great gift? Rodriguez stepped away from the microphone in 1973 and took up a tool belt, thinking that his message, his voice, had gone unheard. In the deepest and richest of ironies, that simply wasn’t so. His voice had been heard very well, on the other side of the world, and in fact helped change an entire society, and affected millions of lives. For most of us, that would be beyond our wildest dreams.